Apocalypse Later, please! is a new section of this website that intends, in these peculiar and dramatic times, to offer a recommendation on films to watch when safely at home: today it’s “Dr. Strangelove“.

Introduction

In these hard, complex and unprecedented times that prescribe (still without an end period) isolation and time indoors in our own houses, we thought that we could’ve suggested ways to use this time at home to turn upside down this “apocalyptic” feeling that at the moment wraps our lives:

we will try to transform it in a way for us all to think, even laugh, “exorcising” our fears.

Everyday (or so) – hoping we stay healthy [oh, this is exactly the feeling that we want to try to exorcise] – we will write about a film that for a reason or another sounds interesting and that deals (even if just metaphorically) with the concept of Apocalypse (and/or the measures taken to contrast it) exploring the ways some films have dealt with it.

We really hope this could bring a smile on your face and help you in using this unexpected (unwanted?) time – hopefully, spoilers-free.

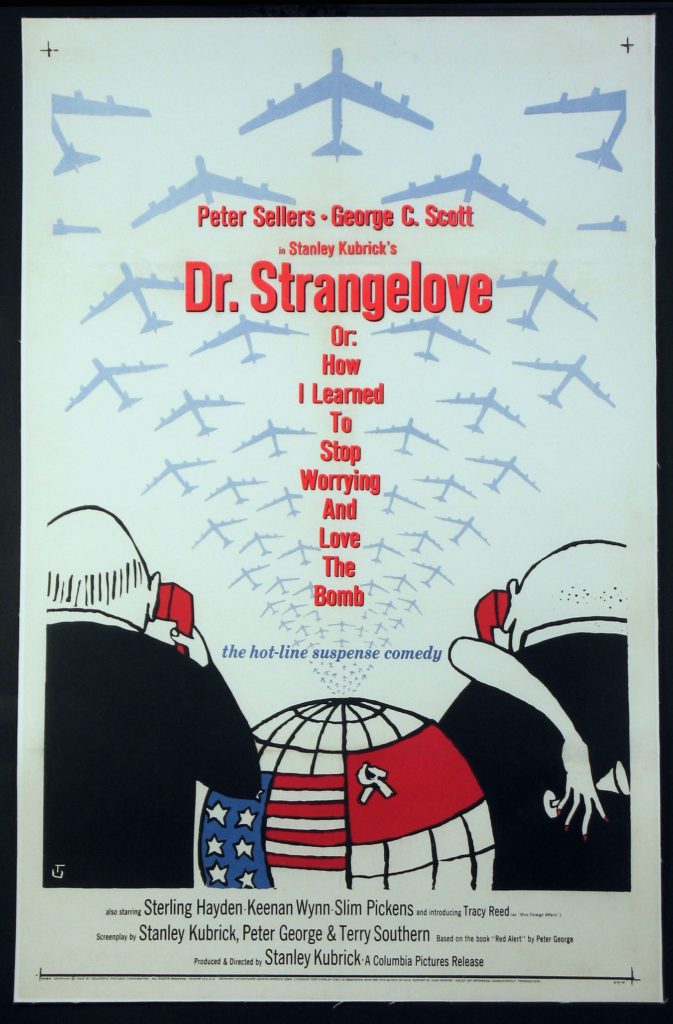

Today’s film: Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.

Man vs. Nature?

Ripper: Mandrake. Mandrake, have you never wondered why I drink only distilled water, or rain water, and only pure grain alcohol?

Jack D. Ripper in “Dr. Strangelove”

Just like for the other films that are or will be part of this website “section”, we are looking at a film that depicts a sort of “apocalypse”.

Although not necessarily as seen by the people but through the perspective of the “secret rooms” of the power, and not as an effect of a natural origin as much as of the human doing (the war), the catastrophe, in this film, seems to be approaching very quickly.

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb is a 1964 film directed by Stanley Kubrick. It’s his seventh film and it precedes 2001: A space odyssey. As usual for Kubrick, the film relies on a very precise and inspired visual scheme that tends to crash the characters under the weight of something bigger than the individuals.

In the film, the historical context is highly symbolical (or at least for us is 2020): it’s cold war time. Men and women were used to living in a context in which a simple “spark” (from one fo the two sides of the curtain) could’ve lead to an escalation so quick that would transform the human condition bringing it to the edge of the abyss (if not beyond!) in no time at all.

Now, imagine this sensation we’re living these days and, even though in a less powerful and visible way, spread it on a long period which lasted for about forty years. Exactly! How did people survive and trust anyone?

One of the narrative elements that make this even more unsettling is the belief by the general Jack D. Ripper [well, the reference is pretty clear, isn’t it?] that the water – key element of our nature – is contaminated. And what could even be more contemporary than something that attacks our everyday life in an unexpected and invisible way? Something that we don’t know where it comes from and we can’t seem to define its characteristic?

Film tone.

Although we know this introduction could almost suggest that the film moves in a slow and dramatic way, the strength of this film – and the reason we’re adding it to the Apocalypse Later, please! section – is to be found in the satirical and comical character of the entire film.

The characters seem caricatures: mad scientists, military majors and generals completely out of their minds, a war room that recalls a circus and then, Peter Sellers who interprets 3 different characters in exceptional way. The editing and the rhythm makes the film relentless. Even the trailer seems to underline the humour side more over than the apocalyptic one:

Even the film title accounts for the satirical turn and the attempt to make people think through a laugh: Dr. Strangelove – or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. How could anyone love something so deadly like an atomic bomb (well, aside from the pilot of the plane)? A way forward could then be to stop worrying and – respecting all the measures our governments ask us to take so that we can get back to our lives as they were before – start laughing exorcising our fears.

Why this film?

We are aware that the choice of this film could be read as slightly off theme and we understand the motivations for such a critique. What we want to turn the spotlight on is the uncontrollable presence of news and texts that intend to offer insight and enlightenments on what is “really” happening: we are referring to a number of hypothesis of people and scholars – or self-proclaimed so – that are trying in every way possible to push their paranoid opinion as reality.

Just like General Ripper does – by not understanding where the danger could come from and its characteristics (in this case it might actually be his own madness) – he invents a human enemy that can indeed be defeated. It’s the case for theories and plots that we can read everyday and that change target every two or three seconds: it’s the Americans! No, it’s the Russian! You’re wrong, it’s the Chinese! Or this or that. All culprit, for these “hypothesis”, of creating the virus in a lab (just like the atomic bomb in the film) to destroy one or another enemy. The dangerousness of these “plots” that are out of control and that feeds on people’s fears and of their will to understand what’s going on, is now on alarming levels.

We don’t doubt that a research and a study on the origins of what we’re living now has to be done and dealt with in the most serious and transparent way possible, nor we are naive and are used to assume that everything we’re told from the official sources is the absolute truth, but we’re convinced that the exploit of “obscure” points in the news, in order to make sure that the suspicion can be pointed at an invisible “hand” that supposedly have created this all, is as dangerous as the virus itself as it hides what we’re really facing.

The “hand” that pulls the strings presumes the fact that the humans are at the centre of the universe and is to be considered responsible for anything that happens. Although true for some issues we’ve created on this planet and for what happens in the film (the war), this thesis seem not to give a good account of the power of nature (and chaos) and life itself. It doesn’t depicts in the right way the strength of nature that always finds its way to “win” against the presumption of “total control” that we, as humans, sometime think to exercise on it. (Jurassic Park, anyone?)

Life always wins.

Exactly like in the film in which the stupidity – a cultural factor, yes, but, provocatively, also a natural aspect of the human condition that characterise even those “secret” rooms pointed by some theories as the invisible “hands” behind this all – and the reality distortions cause a Texas-rodeo-style apocalypse.

And to us, who today are facing this terrible situation, there’s nothing left to do but watching a film and laugh about ourselves and our fears, waiting for our life, our nature to find a way to win this and help us starting again.

You don’t know what film to watch tonight? Please have a look at our Film Alphabet page.

Tired of the news, comments and you are interested in reading film analysis and reviews? Go and check out our Analysis section.